In Mexico you discover new worlds through timeless connections. There are cities here that haven't been populated in over thousand years, and yet when you visit you come to know the people who lived there, from their art, their hopes for corn and rain, their plans for harvests and burials. There are Colonial centers where you can trace globalization from Persia to Arabia to Africa to Spain in the arabesque of a balcony, the pomegranates in a sauce, the gold lavished on a church. But these cities are showcases of the New World: its native craftspeople and farmers, its unfathomable wealth, its artists who decorated alters with angels as their forebears had with feathered gods. The heritage sites of Mexico tells a story; come, let us share them with you.

ZÓCALO, MEXICO CITY

The scale of the Zócalo in Mexico City, is one of the world's largest public squares, is should engulf you in its vastness. Its buildings are like Mexico's greeting committee, mammoth in their proportions. But step inside and the spaces cloak you in time, granting a personal vantage on centuries of civilizations.

One side of the square is filled with the Palacio National, holding the site where Moctezuma II wielded power and the current Mexican president still does. Hernán Cortés and the Viceroys set the palatial style, with courtyards and arches, in the 1500s; Diego Rivera colored it in during the 1930s with human passions of the Aztecs, conquerors, and revolutionaries depicted in his murals.

On another side of the Zócalo stands the Cathedral Meropolitana, consecrated in 1532 as the beacon of New Spain in North America. The structure dates back to 1573 and was completed with Manuel Tolsa's cupola, clock, and upper-façade sculpture in 1813. So graceful is the columned luxury of its interior, so beautiful its Alter de los Reyes, that it whispers of continuous worship. The mood accords with it lineage, since it was built on the ruins of an Aztec religious site that resurfaced in 1978 when a utility worker digging beside the Cathedral struck the pyramid of the Templo Mayor.

Today you can visit and walk between altars to the gods of war and rain at the excavation of Templo Mayor and be reminded that when Cortés arrived here in 1521 he found an affluent metropolis, Tenochtitlán, with some 20,000 buildings, 78 of them standing on the present Zócalo, and a population larger than any European city's at the time. What endures is the beauty of a carving found in the ruins of the moon goddess Coyolxauhqui and the legend of how she was vanquished; it covers an eight-ton monolith, suiting the scale of the Zócalo.

The Aztecs themselves "repurposed" structures, including the pyramid that held Templo Mayor, which had six predecessors on the same platform, dating to the founding of Tenochtitlán in 1325. Around that same year the Aztecs also moved into Teotihuacán, 30 miles north of Tenochtitlán, and turned what had been the most important city in Mesoamerica between 300 and 600 A.D. into their own ceremonial center. By then Teotihuacán, which once housed some 200,000 people in diverse neighbourhoods, was long past its prime. Yet enough remains even now to impress on visitors to this World Heritage Site (named in 1987, as was the Historic Center of Mexico City) the great achievements in science, arts, and architecture of 1500 years ago. Here you will find pyramids dedicated to the sun and the moon, and when you climb them you overlook what once must have been a vast, bustling Zócalo.

The major monument of teotihuacán were oriented to be movement of light, and so was the simple house builtt by Luis Barragán in 1947 in the Tacubaya neighbourhood of Mexico City. The architect was known for his spiritual devotion; his Tlalphan Chapel in Mexico City overwhelms with its emotional power. In the Tlacubaya space, where he lived and worked until his death in 1988, you can see how he distilled all of the Mexican landscape, from pyramids to murals, into modernist intersections of planes, colors subdued and flamboyant, the reach of garden greenery, and the sun-play of the day. Barragán was awarded the Pritzker Prize in 1980, his house and studio, open to tours, was named a World Heritage Site in 2004. Here you pause in the stillness of the architect's reflection.

PUEBLA

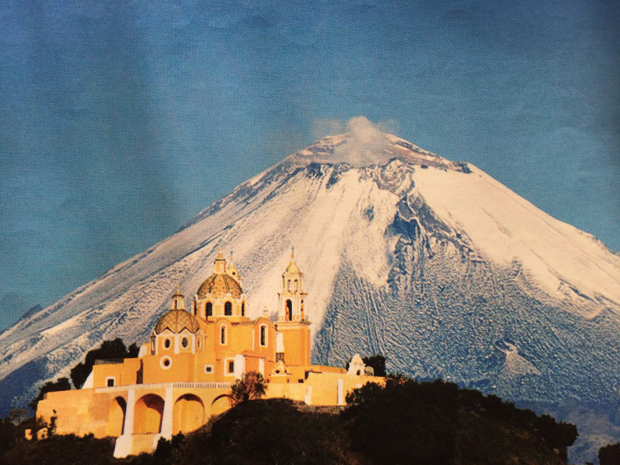

Viewed from a tower of its Cathedral, the tallest in Mexico, Puebla is a panorama of splendour: tiled and gilded church domes, facades and balconies eloquent with Renaissance imagination, and , as their backdrop, the snow-capped, volcanic Popocatépetl. The site was hollow chosen by Spain in 1531 as a way-station between Mexico City and the port in Veracuz, its sumptuouness funded by shipments of Mexican silver and gold.

Details of the Cathedral (built 1574-1648) anticipate the craftsmanship of Puebla's historic center, which was named a World Heritage Site in 1987. The roof is covered with glazed majolica tiles, the Talavera ceramic world that recalls the Moorish decorative legacy in Spain and that is still the pride of Puebla. The alter is carved marble and onyx, its chapels and sacristy a museum of 17th-century Spanish painting. You can examine more tilework, marquetry, and carving in the Museo Bello y González and the Museo de Arte Popular Poblamo, which preserves the convent kitchen where more poblano is said to have been created. Visit also the Capilla del Rosario, a jewel of Baroque art, and the Biblioteca Palafoxiana, the oldest library in the Americas.

The cuisine of Puebla features a parallel complexity. Taste it in the famous mole poblana, a pre-Columbian thickened chile sauce that was enhanced, according to legend, by Sor Andrea de la Asunción with Spanish-introduced spices and nuts. In September, month of both Mexican independence and the walnut harvest, the specialty is meat-filled chiles en nogada, a New-Old World fusion that banners the colors of the Mexican flag in it green pablano chile, white Moorish-descended nut sauce, and red pomegranate-seed garnish.

For visceral refreshment, fix your gaze on Popocatépetl and rive the few miles to Cholula at its base, where the pyramid built over a thousand years, from 300 B.C. to 700 A.D., it crowned by a gold-domed church, added in 1666, and a timeless, stunning view.

About 25 miles north of Puebla, in the smaller Colonial city of Tlaxcala, you'll be dazzled by the gold lavished on every crevice of the Santuario de la Virgen de Ocoltán, a Baroque masterpiece from the 18th century. But 12 miles west of Tlaxcala, at the ruins of Cacaxtla, the Vibrant colors of the painted murals, discovered in 1975 and the largest in Mesoamerica, are perhaps even more astonishing for being a thousand years older.

GUANAJUATO

The muralist Diego Rivera, born in Guanajuato, recalled of his earliest artwork: "I refused for a long time to draw mountians, owing to the fact that although Guanajuato was surrounded by them, I didn't know what was inside them." When his father took him into a silver mine the interior was revealed, and then the boy started drawing mountains.

The mines here supplied half of the world's silver for over two centuries, beginning around 1558 with the opening of Valenciana; they were named a World Heritage Site with Guanajuato in 1988. Rivera grew up amid the architecture of this affluence, the brightly painted ornate homes, domed churches, university, plazas, fountains, and parks. The Museo Casa Diego Rivera preserves the family home and displays a fine collection of the artist's later work.

Another famous "denizen," especially during October's International Cervantes Festival, is Don Quijote, whose Museo Iconográfico del Quijote holds paintings and sculpture devoted to his image, they were collected by Spaniard who fled Franco-ere oppression and include works by renowned artists. Quijote sprang from Cervantes's imagination in 1605, around the same time Guanajuato was being built, and the city seems oddly designed for his dreams, with twisting, steep passageways so narrow it's said that lovers can kiss from balconies on opposite sides.

Dreaminess nestles also in the elaborate Teatro Juárez, which opened in 1903 with a performance of Aida attended by Verdi. Shoppers in the city's many galleries seek silver jewelry and the majolica-style ceramics of the local artist Gorky González.

San Miguel de Allende, about an hour's drive east, is known for its artisan workshops, lovingly preserved colonial homes, and an artists' colony that includes many Americans. At the center of town, the glorious Gothic towers of La Parrogquia church suggest skyward aspiration. They might inspire you to enroll in an art class or craft work-shop offered by the Instituto Allende and another of the city's art schools.

QUERÉTARO

History brought to Querétaro the romance of a great struggle won. Founded in 1531, the city was central to the Spanish conquest, a nexus of religious conversion and brutal subjugation of the native Mexicans sent into the silver mines to the north. But amid the architecture of power and glory that endures here, the seeds of independence were sown in a conspiracy of rebels that included Doña Josefa Ortiz le Dominquez. Wife of the royally-appointed mayor, and thus known as La Corregidora, Doña Josefa became a national hero in 1810 when she was able to alert Father Migel Hidalgo and other organizers of the War of Independence of a plot to kill them.

Today, the 18th-century palace where La Corregidora lived and plotted resistance is, aptly, a seat of elected government, facing the Plaza de la Independencia, the city's main square. It is near the Teatro de la Republica, where Maximilian of Habsburg, the last foreign ruler, was sentenced to death in 1867, and where the current Mexican Constitution was signed in 1917. The Historic Monuments Zone of Querétaro was named a World Heritage Site in 1996.

A personal sense of romance is nourished here by bougainvillea-draped plazas, narrow cobblestone passageways, and the pleasures of strolling and café-sitting in a city of uncommon grace. Among the 18th-century mansions offering accommodations, La Casa de la Marquesa is distinguished by its opulent Mudejar courtyard.

The Templo de SAnta Rosa de Viterbo, a gold-leafed fantasia dating from 1752, was the crowning achievement of Ignacio Mariano de las Casas, whose architectural imprint marks the city. His Convent de San Agustin now houses in its Baroque cloister the Museo de Arte de Querétaro.

In 1750 Father Junipero Serra extended the Franciscan mission into the Sierra Gorda, the mountains that begin about 70 miles north of the city. His five mission churches were named a World Heritage Site in 2003 for their intricately carved and painted facades. They suggest Father Serra's humanism in the mingling of native craft styles and botanical motifs with religious icons. Of his beautiful, remote outpost Father Serra said, "In this place, the land and the skies sing to their Creator."

MICHOACÁN

The majestic architecture of Morelia witnessed profound transformation of the city over four and a half centuries without a wink of its grand arcades of a blink of its Baroque excess. Founded in 1514 by Spanish aristocrats who wanted to indulge their tastes away from native villages, the pink quarrystone city center has remained intact, drawing recognition as a World Heritage Site in 1991 and the continuous attention of art students.

The central plaza, rimmed with arcade-connected mansions, saw bloodshed during the War of Independence, and afterward, in 1828, the city was renamed to honor its native son, the millitary hero José Maria Morelos y Pavón. The plaza itself bears remembrance of wartime executions in its name, Plaza of Martyrs. It is now a lovely place to sit at a café or under a tree and enjoy a view of the twin-spired Cathedral, which has a 6,400-pipe organ and hosts the International Festival of the Pipe Organ every May.

Visitors can also enjoy two non-structural aspects of craftsmanship introduced by the Spanish. One is candy-making, once a specialty of the convents and now of the Mercado de Dulces, where vendors will tempt you with nut brittles, fruit pastes, and the sweetened coconut treats called "cocadas". The other was craft specialization, with villages encouraged, particularly by the missionary priest Vasco de Quiroga of Pátzcuaro, to develop their commitment to one set of skills. The Casa de las Artesanias displays the quality that was sustained this way; its wares, labeled by village, may prompt excursions from Morelia to Santa Clara del Cobre for Copperware, to Uruapan for lacquered platters and bowls, and to Pátzcuaro, a scenic lakeside market town for the area's weaving, embroidery, pottery, and carved furniture.

The most brilliant excursion, by far, is that of the monarch butterflies who come from allow over North America to winter in the forests about 80 miles east of Morelia. In January and February their orange hibernation covers the trees; when the days warm, in February and March, the begin to flutter again. A trip to El Rosario, or another of the four butterfly reserves, can add to your enjoyment of historic Morelia the thrilling evanescence of a season in the sun.

JALISCO

In the early 19th century Bishop Juan Cruz Ruiz de Cabañas commissioned the architect Manuel Tolsá to design a haven for orphans and others in need. The house of Mercy that opened in 1810 was a grand embrace in the Neoclassical style, with 23 patios connected by 78 corridors - an orderly, graceful world invaded by military chaos in the War for Independence and again during the Mexican Revolution but mostly a refuge, home to as many as 3,000 orphans at a time.

In 1937 José Clemente Orozco, native son of Jalisco state, was invited by the local government to decorate the building's main chapel. With the theme of "The Conquest of Mexico" he painted 53 murals in two years, filling the space with the power of people caught up in historical and moral struggles, and culminating in the dome with "The Man in Flames," a depiction of man lit and consumed by ideals. Orozco's artistic and technical achievement became known as "Mexico's Sistine Chapel." In 1983, after the orphanage had moved, the building became and Instituto Cultural Cabanas, where the experience of the murals is enhanced by undreds of Orozco's preparatory drawings; in 1997 it became a World Heritage Site.

View more of Orozco's murals at the Palacio de Gobierno, where the artist painted a searing image of Independence hero Miguel Hidalgo and flanked it with a caricature of government called "Political Circus" and a clergy-army alliance dubbed "The Brutal Forces." In the city's La Scala-inspired Teatro Degollado, opened in 1866, the mural depiction of a Dante canto, created by Jacobo Gálvez and Gerardo Suárez, is only upstaged in vividness by weekly performances of the Ballet Folclórico.

You can trace the local arts of pottery and glass in the Museo Regional de la Cerámica in suburban Tlaquepaque. The neighboring village of Tonalá becomes a showcase of these, as well as wrought iron and wood carving, at its Thursday market.

Travel to Tequila, 35 miles northwest, and you'll enter the landscape of blue agave named a World Heritage Site in 2006. The juice of the cactuslike plant was fermented to make pulque for thousands of years before the Spanish added the distillation the yields tequila. At Tequila Cuervo you'll see the legacy painted large in Gabriel Flores' extraordinary mural, "Mythology and History of Tequila."